So many reviewers, columnists, and performers are bemoaning the recent bad behavior of Broadway audiences. It’s as if having people in the audience who distract other audience members, upstage the show, and act in ways that detract from the live stage performance are something new. These actions are not. Such behavior is actually normal in the American theatre. If, somehow, you manage to not have anyone act inappropriately, then you truly have had a special live theatre experience.

Often Isolated

At any given performance of any play, there are small, isolated displays of rudeness by audience members. Most are fairly innocuous and go unnoticed by the majority of those in attendance, monitoring the house, and performing on stage.

Incidents such as unwrapping and consuming food, using chewing tobacco, commenting on the action or a line in a play, or discussing the day’s events with a friend are done habitually and have been a part of the theatre for centuries. Note, none of these types of poor behavior involve technology. Incidents with technology have been occurring for less than a half-century.

Audience Control

Controlling audience behavior and encouraging proper decorum has been an issue in the US since the late 18th century. Many critics and commentators, including Washington Irving, Walt Whitman, and Frances Trollope, wrote about the audacity, poor manners, and outrageous actions of audiences in New York, Washington, D.C., Cincinnati, and other parts of the country.

In 1802 that when he went to see a show at the Park Theatre in New York City, Irving wrote, “Although constables were stationed in the gallery to keep order, they did not do so. The gallery gods whistled, shouted, hissed, and groaned. They showered spectators in the pit with apples, nuts, and gingerbread. The spectators in the boxes were not so noisy but for them too playgoing was a social occasion. The belles simpered and coquetted. The beaux studiously wielded their glasses and ostentatiously ignored the play. The men in the pit suffered drip from the chandelier and barrages from the gallery, but their own behavior was not the best; they stood on the benches before the curtain went up like spectators at a football game before the kick-off.”

Trollope, who went to theatre throughout the U.S. in the early to mid-nineteenth century, was in the nation’s capital during a performance when she observed, “One man in the pit was seized with a violent fit of vomiting, which appeared to not in the least to surprise of annoy his neighbors; and the happy coincidence of a physician being at that moment personated on stage, was hailed by many in the audience as an excellent joke, of which the actor took advantage and elicited shouts of applause by saying ‘I expect my services are wanted elsewhere.’”

She went on to comment on the many politicians in the audience, saying, “The spitting was incessant, and not one in ten of the male part of male part of the illustrious legislative audience sat according to the usual custom of human beings; the legs were thrown sometimes over the front of the box, sometimes over the side of it, here and there a senator stretched his entire length over the bench, and in many instances the front rail was preferred as a seat.”

Such activities would not be tolerated today. However, humankind being what it is, there is, due to the very different natures of each person and the fact that the U.S. is not a police state, bound to be behaviors amongst theatre patrons that annoy other theatregoers as well as, at times, the actors on stage.

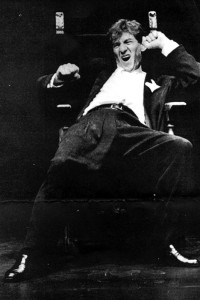

Ian McKellen and Acting Shakespeare

It was in the 1980s that I went to see Ian McKellen in his one-man show Acting Shakespeare at the Charles Playhouse in Boston. The show was being performed in the theatre’s 500-seat house and the performance was sold out. I had seats in the second row and was but 10-feet away from the actor.

When McKellen took the stage to applause he launched into one of Shakespeare’s famous soliloquys. I can’t remember which one because as the great actor began the speech, he was joined by an elderly gentleman sitting in the audience left section. That man recited the piece word for word with McKellen.

You could feel the entire energy of the house change, as we listened to this odd duo that featured the rich voice and amazing interpretive skills of one of the greatest actors of the English speaking stage and the shaky but enthusiastic tones of an aging lover of the Bard.

After the first speech was over, McKellen greeted the audience and introduced the show. He then launched into his second piece, which was a reading of what is written on the great playwright’s tombstone. The actor focused stage left on the imaged tombstone, his back to the man who had recited the initial passage with him, and began, reciting, and the elderly gentleman, once again, join him-

“Good frend for Jesus sake forbeare to

Digg the dust encloased heare…”

Then McKellen thrust out his right hand towards his unwanted fellow performer, stopped reciting, and without turning towards the interrupter said, “I say, old chap, I believe the people came hear tonight to hear just one man recite Shakespeare.”

With that pronouncement, the audience applauded, the old man laughed, and the rest of the evening was McKellen performing in the manner he had intended, alone.

Richard Wagner and Thomas Edison

It was the great opera composer and producer Richard Wagner who was instrumental in devising a few simple but fairly effective methods of controlling audience behavior. He did so by utlizing specific design elements in the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which was built in the 1870s.

First, he created a seating arrangement that made audiences focus on the stage by eliminating the side boxes, which were often the source of interruptive behavior. He also lengthened the distance between the stage and audience and placed the orchestra in a sunken pit so that they could not be seen.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, he dimmed the lights in the house, which meant the only part of the theatre that was illuminated was the stage. By blacking out the audience, he greatly diminished the opportunities for theatregoers to interact and misbehave, while his other innovations demanded that audiences focus on what was happening on stage.

In 1879, Thomas Edison created the first successful electric light. By the 1880s, cities were being wired for electricity and by the 1890s theatres had begun to make the transition from gaslight to electric.

Electric light gave us much more control over audiences by giving stage practitioners a means to focus audience attention on specific parts of the stage, including upstage and stage right and left areas that gaslight could not effectively illuminate. The new lighting used in productions, as well as in the complete extinguishing of house lights during a performance, demanded that audiences focus their attention on the show and not on one another.

Technology Controls and Out of Control

Ironically, much of the same technology that gave theatre producers more control over audiences is also responsible for now distracting audiences. Powered by an electrical charge, our mini-computers, which we still often refer to as “phones,” have become the primary distractive elements in today’s theatres.

Whether it’s someone illegally recording a performance, taking pictures of a show, surfing the Internet, or texting a friend, lover, or babysitter, these devices, which now light up previously darkened auditoriums, have become a major nuisance. Along with all of the distractive activity they inspire, they also, occasionally ring in some manner when someone forgets to shut them off or mute them.

It’s very perplexing to those who work in the theatre. These devices have clearly accelerated loutish behavior.

Hand of God

Recently, a bad behavior incident, which was widely written about and discussed, involved a young man who was attending a performance of Hand of God on Broadway. Prior to the start of the show, the man went on stage and plugged his cell phone charger into an electrical outlet on the fairly realistic set. Of course, the outlet was not practical, but the theatergoer saw a representation of reality on stage and went with it.

This type of behavior, which is the kind of thing that simply mystifies many of us and totally bewilders anyone working in the theatre, is not uncommon. Patti LuPone recently snatched a phone from someone texting during an Off-Broadway show in which she was performing, Madonna drew criticism for texting during Hamilton, and many other incidents have been chronicled with increasing frequency.

The offender during Hand to God was a 19-year-old named Nick Silvestri who said in a press conference held by the producers, “I don’t go to plays very much, and I didn’t realize that the stage is considered off limits.” He also noted, “I’ve learned a lot about the theater in the past few days — theater people are really passionate and have been very willing to educate me. I would like to sincerely apologize to the Broadway community.”

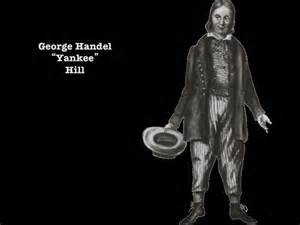

Typical Yankee Character

What many do not understand, especially those in the theatre, is that this behavior is typically American, and we should expect it and take positive steps to change the culture that engages in it. In the first successful American play, The Contrast (1787), playwright Royall Tyler created a character who mirrored the uneducated, well-meaning, sincere, and simple American. This was the Yankee character; a type that would be popular on the American stage for close to a century.

In The Contrast, Jonathan, who is the Yankee character, talks about going to see the play School for Scandal. As he accounts what he witnessed on stage, it becomes evident that he thinks he’s viewed real life playing out in front of him. It’s a very funny monologue, partly due to the innocence and ignorance of the character.

Although not all of those who offend are like the Yankee character, Mr. Silvestri and others who are connected to him by their lack of knowledge regarding the theatre and what’s expected of them, are. Remember, cellphone technology is new to everyone and constantly developing, and those who have grown up with it see it as essential and natural to their lives as eating, breathing, and speaking.

Please Check Your Devices?

Finally, and this is a radical idea for curbing the problem, perhaps it’s as simple as having a place for people to check their devices when they are going to a show. It sounds cumbersome for sure and 99% of those who have cells, which is about 100% of the public, would resist it.

In lieu of such an invasive and time-consuming practice as checking cellphones, perhaps a campaign to really educate people about theatre decorum and phones would be in order? Whose job would it be to educate theses people?

It would be the job of those of us in the theatre. After all, they are coming into our house and we set the rules. That being the case it’s our responsibility to make sure that those rules are clearly understood and enforced.