Advertisements for an anonymous magician appeared in English newspapers in January of the year 1749. The ads described what sounded like impossible and miraculous acts to be presented. One example:

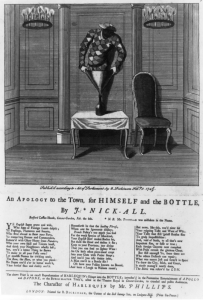

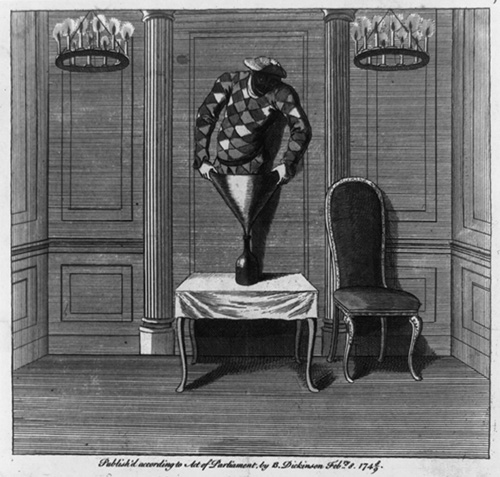

At the New Theatre in the Hay-market, on Monday next, the 16th instant, to be seen, a person who performs the several most surprising things following, viz. first, he takes a common walking-cane from any of the spectators, and thereon plays the music of every instrument now in use, and likewise sings to surprising perfection. Secondly, he presents you with a common wine bottle, which any of the spectators may first examine; this bottle is placed on a table in the middle of the stage, and he (without any equivocation) goes into it in sight of all the spectators, and sings in it; during his stay in the bottle any person may handle it, and see plainly that it does not exceed a common tavern bottle.

Those on the stage or in the boxes may come in masked habits (if agreeable to them); and the performer (if desired) will inform them who they are.1

The unknown conjuror was promising to play a walking cane somehow as if it were any known instrument, squeeze himself entirely into a wine bottle in full view of the audience, and identify any audience member by name even while masked.

A large audience assembled for this event on the evening of January 16th. One of the king’s sons, the Duke of Cumberland, was present2. The lights were brought up, but the performer who booked the space and publicized the show was not present. There was no music or other entertainment – nothing. The audience became restless and rowdy. The theatre manager, Samuel Foote, tried to calm the crowd. There was shouting back at Foote about paying more to see the conjuror stuff himself into a pint bottle instead of a one-quart wine bottle. The crowd became unruly.

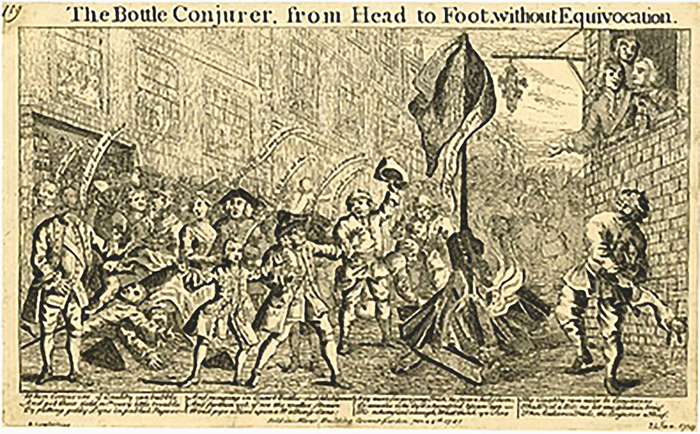

An audience member threw a lit candle onto the stage. Some of the audience began to leave. Some were so angry that they stayed inside and attacked the theatre. Benches were ripped up, scenery was vandalized, curtains shredded, and box seats were destroyed. The crowd carried debris from the theatre out into the street and started a bonfire.3

“One party, however, staid in the house, in order to demolish the inside, when the mob breaking in, they tore up the benches, broke to pieces the scenes, pulled down the boxes; in short, dismantled the Theatre entirely, carrying away the particulars above mentioned into the street, where they made a mighty bonfire; the curtain being housed on a pole by way of a flag.”4

It was a perfect storm of high-publicity and mismanagement. High expectations had been created, a large crowd gathered, and then nothing was delivered. John Potter , the owner of the theatre, had suspected something was not correct. Theatre manager Foote, was under suspicion for creating the hoax, but claimed that he had warned Potter that all of the arrangements had been made by some “strange man.” 5

The incident became legendary. “The Bottle Conjuror” became a metaphor for the gullibility of the London population.

It was asserted by one paper that the conjurer had been ready and willing to appear on the fatal night, but just prior to the performance a gentleman begged him for a private view. The conjurer consented to crawl into a bottle. The moment he had done so the gentleman played on the unhappy conjurer the same trick which the fisherman in the “Arabian Nights” found so efficacious with the genie. He quietly corked up the bottle, whipped it in his pocket, and made off.” Thus the poor man being bit himself, in being confined in the Bottle and in a Gentleman’s Pocket, could not be in another Place ; for he never advertised he would go into two Bottles at one and the same time. He is still in the Gentleman’s custody, who uncorks him now and then to feed him ; but his long confinement has so damped his Spirits that instead of singing and dancing he is perpetually crying and cursing his ill Fate. But though the Town nave been disappointed of seeing him go into the Bottle, in a few days they will have the pleasure of seeing him come out of the Bottle ; of which timely notice will be given in the daily Papers.”5

It is not known who perpetuated the hoax. However, some authors from the period believed that Second Duke of Montagu, John Montagu, was the culprit. He was reported to have claimed that “it went so far, that if a person advertised that he would creep into a quart bottle, he would procure an audience.” It is said that this led to a disagreement, and then a wager, which led the Duke to run the above advertisement in the papers. 6

Sources:

1 Ryan, Richard; Talma, François Joseph (1830), Dramatic table talk, or, Scenes, situations, & adventures, serious & comic, in theatrical history & biography, 3, London: J. Knight & H. Lacey, pp 69-70

2 Clery, E. J. (1999), “The Rise of Supernatural Fiction, 1762–1800“, Volume 12 of Cambridge studies in Romanticism (illustrated ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66458-6, p 29

3 Ryan, Richard; Talma, François Joseph (1830), Dramatic table talk, or, Scenes, situations, & adventures, serious & comic, in theatrical history & biography, 3, London: J. Knight & H. Lacey, p 72

4 Oldschool, Oliver, Esq. (1806), Port Folio, Vol. 11. Philadelphia: John Watts. p 312.

5 Walsh, William Shepard (1909), Handy-book of Literary Curiosities, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co. p 477

6 Ryan, Richard; Talma, François Joseph (1830), Dramatic table talk, or, Scenes, situations, & adventures, serious & comic, in theatrical history & biography, 3, London: J. Knight & H. Lacey, p 69